Brain Size May Indicate Risk Of Eating Disorder

Teens with anorexia nervosa have bigger brains than teens without the eating disorder, new research from the University of Colorado’s School of Medicine has found.

Teens with anorexia nervosa have bigger brains than teens without the eating disorder, new research from the University of Colorado’s School of Medicine has found.

Researchers discovered that adolescents with anorexia had a larger insula – the part of the brain that is active when tasting food – as well as a larger orbitofrontal cortex, which is the region responsible for signaling cues about satiety and fullness.

A predisposition?

Having a bigger brain – as seen in both children with anorexia and adults who had recovered from the disease – could predispose a person to developing an eating disorder, said Guido Frank, assistant professor of psychiatry and neuroscience and CU School of Medicine.

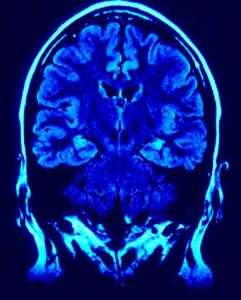

The researchers analyzed 19 adolescent girls with anorexia nervosa using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and comparing the results with scans of 22 young women in a control group.

“While eating disorders are often triggered by the environment, there are most likely biological mechanisms that have to come together for an individual to develop an eating disorder such as anorexia nervosa,” Frank said in a statement.

Brain differences

Since the study suggests that an anorexic’s brain surface area is larger in two areas that regulate taste and hunger, this could account for why these individuals stop eating faster before they have eaten enough, researchers said.

The right insula not only processes sweets, but also integrates body perception – which could be a clue as to how it might contribute to false perceptions or negative self-talk in anorexics.

The study supports other research that found adults with anorexia – as well as adults who have recovered from the illness – also had differences in brain size than adults without the disorder.

Results of the University of Colorado study are published in the Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry.

Source: University of Colorado

Eating Disorder Self Test. Take the EAT-26 self test to see if you might have eating disorder symptoms that might require professional evaluation. All answers are confidential.

Eating Disorder Self Test. Take the EAT-26 self test to see if you might have eating disorder symptoms that might require professional evaluation. All answers are confidential.